How To Select Your Market Entry Strategy

We are often approached by wannabe entrepreneurs for help with market research and forecasting. Whilst this is critically important in order to assess if a viable opportunity even exists, this is only the beginning of the planning process. Once you have done the basic market research that confirms that an opportunity in your chosen market actually exists and put together some basic financial forecasts that show that this opportunity can be monetised, the real challenge for small business owners begins. It is much easier to spot an opportunity than to develop a credible strategy whereby you can exploit that opportunity. Indeed, the chances are that you will not be able to pursue every opportunity that you find. Successful entrepreneurs, in my experience, have a well-stocked opportunity register, but only pursue opportunities in segments of their chosen market in which they are confident that they can establish and defend a strong market position.

The question then for anyone faced with the difficult task of choosing which opportunities to pursue and which to forgo is "how can I select a strategy for my start-up business that will establish and sustain a strong market position?". This article is dedicated to explaining the five-step method that we use with our clients to help them select the most appropriate strategy to achieve their goals.

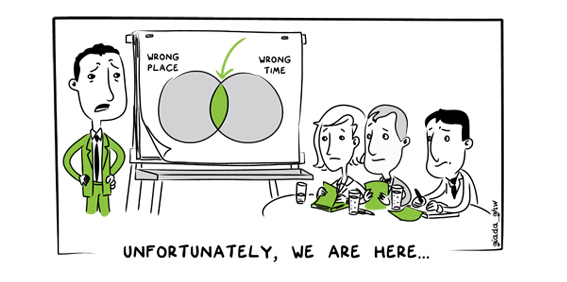

Deciding on a market entry strategy depends in large part on what you expect the competitive response to be. If the new product, service or business model you put in place has any significant impact upon your competitor's performance or represents a significant opportunity for them to develop their businesses, you can expect that they will respond to you sooner rather than later. To some extent, however, your choice of entry strategy can help to shape the nature and impact of their response. Since as a small business it is unlikely that you have access to the kind of resources necessary to go toe to toe with your competition, the idea is to use creativity and imagination instead of money or manpower to compete successfully. Debilitating competition against a well-resourced competitor would be fatal to any market entrant, but by using speed, skill, and surprise, it is possible for a new market entrant to carve out a significant place for themselves.

Step 1: Identify The First Few Customers for Your Business

The starting point for any market entry strategy is to identify the customers within the market that you intend to address first. The challenge is to then verify with these "seed customers" that your offering is attractive to them at the price point that forms the basis of your financial projections. Usually, this is done with at least a minimum viable product (MVP), but it may well be that you need to elicit the support of these "seed customers" in principle before the product or service has even been developed.

This commitment from "seed customers" is an affirmation of market acceptance of the new product service or business model. Without this affirmation from customers, it would be foolhardy to proceed and you might be better served going back to the drawing board. I recommend to my clients that they get the names of at least five customers with a demonstrated willingness to buy before they commit time and resources to an opportunity. Ideally, they would demonstrate willingness to buy with an order. However, if you can't get an order, get a letter of intent or at the very least a written expression of interest. If you can't get at least a written expression of interest from five customers, you need to go back to the drawing board, hopefully having learned something in your interaction with real customers about what you need to do differently to achieve this "demonstrated willingness to buy".

Step 2: Identify The Sales Process For These Customers

When planning your startup strategy, you need to identify who specifically is involved in the buying process and the steps required to move those involved in the buying process forward towards the purchase. You need to get a feel for their needs and interests as far as your offering is concerned and ensure that your sales process addresses those needs and interests. In the book The New Strategic Selling by Robert Miller and Stephen Heiman, the authors identify four distinct people or groups that are typically involved in the B2B/B2C sales process. These are:

- Technical Buyer – The role of this person is to screen out and evaluate suppliers' products and services.

- Economic Buyer - The role of this person is to ultimately sign off the purchase of the suppliers' products and services.

- User Buyer – The role of this person is to use and benefit from the suppliers offering.

- Coach – This is a person who can guide the seller and make and keep you informed throughout the process.

The sales process for B2C and B2B products and services are different. The sales process for many B2C offerings is shorter than for B2B and all four roles might be fulfilled by one person. In big-ticket B2B products and services, the sales process might take many months or even years and several people might be involved in fulfilling each role. Whether you are looking to market a B2B or B2C product or service, mapping out your sales process is a crucial step in scaling up your sales efforts beyond your initial attempts to attract "seed customers".

Step 3: Identify Your Immediate Competitors

There are three groups of competitors that you ought to be at least aware of when determining your market entry strategy. These are:

- Primary or Direct Competitors - These are the businesses who your customers can approach to get a product or service that fills the same need as yours does. These businesses will probably be the ones who you find yourself bumping up against in your search for new customers. For example, if you are a marketing consultancy, your direct competitors would be other marketing consultants or consultancy firms with the same specialty.

- Secondary or Indirect Competitors - These are the businesses who may not go head-to-head with you, but who are targeting the same general market. Just to illustrate the difference between direct and indirect competition, a pizza parlour competes directly against other pizza parlours but indirectly against a business selling Fried Chicken.

- Potential Competitors - These are companies who might be moving into your market and who you need to prepare to compete against. For example, if you operate an independent coffee shop you will need to prepare to compete against national coffee shop chains, even if they are not yet in your market.

This step goes beyond simple awareness of the names of these businesses. We would recommend that you create and maintain a competitor profile for all of your direct competitors. Most small and medium-sized businesses simply do not conduct this type of analysis systematically enough. As a result, many businesses are at risk from dangerous competitive blindspots due to a lack of robust competitor analysis.

Step 4: Assess The Commitment and Capacity of Competitors to Respond

The propensity of your competitors to respond to your new business proposition will be determined by the degree of threat that competing organisations feel by your entry into the market. The degree of threat depends upon how they view the competitive significance of the market. The more committed your competitors are to a particular market, the more vigorous the competitive response is likely to be. The following three questions should help you to evaluate the level of their commitment.

- Is this market important to them? - If this is a single unit operation whose whole business depends upon the market you have just entered, you can expect a fight. The higher the stakes and the stronger the position in the market, the more important this market is likely to be.

- Have they been increasing commitment in this market? - Whilst this might be somewhat difficult to discern from the outside, there are a few telltale signs of increasing commitment. Examples include relevant new product announcements, increases in visible resource allocation (e.g. marketing spend) and increased fixed asset commitments to serve this market. The greater the increase in commitment to the market, the more vigorous their competitive response is likely to be.

- Have they invested heavily in this market? - If your competitors have made a significant investment to serve this market in such things as, for example, plant and equipment, training or their brand, you can be sure that they will respond to any significant encroachment upon "their" territory.

Even with the greatest desire in the world, without the resources, appropriate skills or technologies a competitor cannot really respond to your entry into the market. The following four questions will give you some indication of a competitor's capacity to respond to your move.

- Do They Have Available Slack In Their Business? - Whilst this might seem somewhat difficult to assess, there are a few indicators that would give you an idea of their capacity to mount an effective response. Some of the indicators that might cause you to feel nervous are large sums of cash at hand on their balance sheet, demonstrated ability to take on large challenges and excess capacity. On the other hand, if there is some internal turbulence in the competing business, such as they are being targeted for purchase or takeover or they have recently lost key personnel, then the chances of them mounting an effective response are diminished.

- Is Their Current Position Strong? - The stronger the current position of your competitors, the more likely they are to be able to mount an effective response. Look at some of the key financial ratios and conduct a benchmarking exercise. Have your competitors demonstrated an ability to consistently achieve superior performance? How does their team compare to yours under the harsh light of objective scrutiny? How does their reputation compare with the other businesses operating in the market?

- Can They Easily Match Your Move? - Obviously, the easier your move is to match, the more likely it is that competitors will do so. Can competitors easily access the same infrastructure, talent and enabling technology that your business uses? Are switching costs high or low for customers? What are the risks for customers in using a competitor offering?

- Is Their Cost of Defence Largely Sunk? - Do competitors already possess some or all of the assets, talent or technology required to mount an effective defense? If so, they will be more able and motivated to defend their position.

Based upon the level of capacity of your competitor and their level of commitment to the market, you should have some idea of the scope and intensity of response that you can expect from any competitive move you make against various competitors.

5. Select The Most Appropriate Market Entry Strategy

According to McGrath and McMillan in their classic book "The Entrepreneurial Mindset", there are broadly four kinds of entry strategy available to you. These are onslaughts, guerilla campaigns, feints and gambits:

Onslaughts

An onslaught as the name might suggest is a direct, aggressive entry into the market. This is typically an expensive, high commitment move to capture significant market share. Before considering an onslaught, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you have or can you make a greater commitment to this market than your competitors?

- Is your entry into the market perceived as credible by informed observers?

- Do your competitors have attractive alternative opportunities they could explore?

- Do you enjoy the support of well-positioned allies such as key distributors, customers, suppliers or relevant government agencies?

- Have you reinvented the rules for your industry, leaving your competitors at a significant disadvantage?

- Are your competitors in the midst of an internal crisis that is preoccupying management?

The more times you can honestly answer "yes" to these questions, the more suitable an onslaught might be. However, it's important to recognise that mounting an onslaught might be beyond the existing resources of your business. For small businesses, especially when pitted against businesses with more resources, it can be difficult to sustain an onslaught for long enough to persuade incumbent competitors to withdraw, to establish first-mover lockout or at least to sufficiently frighten the competition so as to deter any expansion in these markets. If you have to give up before you have achieved these aims, you will be vulnerable to a counter-attack.

Guerilla Campaigns

A more subtle alternative to an onslaught is a guerilla campaign. The objective of a guerilla campaign is to build a position in the market one niche at a time, progressively expanding from one niche to another as your position consolidates. Thus, rather than seeking to dominate a mainstream market, using a guerilla strategy you might selectively sell to a niche which you will either dominate or which you can quickly abandon if you attract competition from a major player. This type of niche approach is particularly useful for new entrants as they tend to be less visible and less threatening than an onslaught. To establish if you would be well served to adopt a guerilla strategy, ask yourself the following questions:

- Are there sizeable niches within your target market that are currently poorly served by existing offerings?

- Can you rapidly achieve a decisive share of the niche market which you will then be able to defend from the subsequent competition?

- Are customers in different niches in the market vocal about being poorly served or overcharged? Are the existing providers listening?

- Can competitors easily match your offering or would their size make it difficult to cost-effectively provide the additional product or service attributes you offer?

- Are customers in these niches willing and able to pay a premium for the additional product or service attributes?

The more times that you are able to honestly answer "yes" to these questions, the more a guerilla campaign might work for you.

Feints

If the competitors which concern you the most are engaged in multiple markets or a diverse range of products or services, then you have the opportunity to use a feint to influence how they react. A feint involves engaging your competitor on two fronts. It is a direct attack against an area that is highly important to your competitor. However, unknown to your competitor, your true purpose lies elsewhere. McGrath and McMillan give a great example of a feint in The Entrepreneurial Mindset. There they relate the story of a small candy manufacturer they had observed in Eastern Europe during the 1990s.

"We observed a small, scrappy candy manufacturer in an emerging economy using feinting to great advantage. Although his primary business was manufacturing hard candy and chewing gum, he also ran at break-even a toffee candy plant. In reviewing his portfolio of businesses, we asked why on earth he would run a small scale funds consuming toffee plant when the rest of his businesses were highly profitable and enjoyed strong regional growth. "Simple", he replied. "I'm not worried about local competition in candy and i'm not really interested in the toffee business. But every so often, managers at a large multi national toffee company, which dominates the regional market for toffee, get the idea that they would like to enter the candy business here. The minute I get wind of it, I drop my toffee prices in a hurry. I might lose money for a while, but for every dollar I lose, my competitor which is fifty times our size, loses fifty dollars, which they have to explain to their head office overseas. It doesn't take long before they get the message and back off from the candy business".

Feints can succeed with little investment, but the threat must be credible. Your feint's credibility is a function of your perceived intentions: the greater the apparent amount of your investment, the more hostile and credible your competitor will consider your attack.

Gambits

A gambit is a term taken from chess in which a player knowingly sacrifices a piece to gain strategic advantage. In competitive exchange, you visibly retreat or withdraw from a particular niche or from a particular product or service, with the express intention of prompting your competition to expand into it. Meanwhile, you focus your attention on a more profitable niche. The whole point of a gambit is to sacrifice something of lesser value in order to take something of greater value.

These are the basic strategies that your business could employ as you prepare to enter a new market. Of course, your strategy may be a combination of some or even all of these moves. The competition within your chosen market will then unfold as a series of offensive and defensive moves until either you or your competitors achieve a decisive market position. It is critical in order to achieve or maintain a significant position in your chosen market to stay on top of both your position and the position of your rivals. This can be difficult and time-consuming for small business owners who sometimes lack the skill but often lack the time and inclination to concern themselves too much with strategic thinking. If that describes your situation, then contact Continuous Business Planning today. Our business support service will help you stay on track and to remain one move ahead of the competition.